Searching for a Lost Way of Life

Hello Everyone!

I’m here to introduce you to another member that recently joined OLR. Mario has a fascinating story that is becoming more and more common as young adults turn away from what we are being taught by society to pursue A New Way of Life.

In actuality, this New Way of Life that we talk about is a very old way of life that has been forgotten by the modern man with all of his knowledge and science. It is a way of family, faith, and farming; a way of reliance on each other and God instead of ourselves; a way of taking care of the earth and animals as we were commanded in Genesis.

You’ll be hearing more from Mario on future journal entires and through the OLR social media (hopefully soon!). With his help we will provide you with more information and current events about homesteading across the globe, along with The Catholic Land Movement that has arisen.

Below is his testimony for you to enjoy and ponder.

Until next time, God Bless.

Tyler Straight

OLR Design & Outreach

SEARCHING FOR A LOST WAY OF LIFE

By Mario John Chris

Four months ago, I discovered Our Lady’s Ranch while searching online for Catholic homestead communities. I had come to realize that, in my twenty-seven years, the typical pursuits of our modern world never quite gave me peace.

After earning my bachelor’s degree in engineering, I worked for a couple years as a software developer at a startup while also moonlighting as an audio engineer at various recording studios. Finding my work unfulfilling, I returned home and completed my master’s degree in creative writing, which gave me the opportunity to teach freshman rhetorical writing for a few semesters.

I stopped moving, that I may stop being followed.

I admit, the novelty of each new experience afforded me temporary pleasure. But there is something to be said for the greater viability of a life dedicated to the well-ordered fulfillment of one’s duty than that of a life spent chasing attractions. As Haruki Murakami writes in his novel Kafka on the Shore, “People soon get tired of things that aren’t boring, but not of what is boring.” I owed the diversity of my résumé to the sense of dissatisfaction that followed me wherever I went. And so, I stopped moving, that I may stop being followed.

Tiziano Vecellio’s painting depicts Sisyphus, Greek mythological king condemned to push a rock uphill for eternity.

I stepped away from my lectureship at the university, and the ensuing silence opened my heart to God’s voice. During this hiatus, my spiritual life flourished, and God planted in my heart the desire for a theocentric agrarian lifestyle. I began to hope that I might attain the lasting serenity and honor I had been looking for.

In his book The Human Zoo, zoologist Desmond Morris outlines the historical shift from tribe to super-tribe: “The crowds became denser, the elite became eliter, the technologies became more technical. . . . As human relationships, lost in the crowd, became ever more impersonal, so man’s inhumanity to man increased to horrible proportions.” Many of us city-dwellers have witnessed these phenomena. The sidewalks bustle with strangers, and not one of them greets another, for his eyes are fixed on the cell phone in his hand, a technology which claims to connect us but in reality isolates us from each other and from our Maker. I especially lacked any sense of tribe or clan since all of my prior workplaces had been void of Catholics. Not surprisingly, there arose within me the longings of an exiled nomad. More importantly, I wished to one day start my own beautiful family, and I feared that any children God blessed me with might suffer a similar loneliness.

The world has, in a word, overcomplicated things.

How are Godfearing children to fit in with peers who don’t think twice about God? Not unlike the Church, the average person is in favor of liberation—however, he fails to see that freedom originates in obedience to God. And again, like most of the world today, the Catholic hopes to create a safe space for his children. But whereas the secular safe space aims to protect the child’s feelings, even from the challenges of moral instruction, I sought an environment that would promote the wellbeing of children’s souls, an environment free from lasciviousness, crude humor, and indiscreet media.

Nor does any political platform seem to make room for Catholic social teaching. For example, I aspire to take seriously my role as a steward of God’s creation, but this philosophy is incompatible with most secular ideas about environmentalism, which are either hypocritical (e.g., touting electric vehicles as eco-friendly even though their batteries depend on cobalt mined under horrific conditions in the Congo), misguided (e.g., encouraging human population control as a means of sustaining an earth which was created for man to inhabit), or reckless (e.g., disregarding every natural resource as yet another free market variable that will take care of itself). The world has, in a word, overcomplicated things.

I felt cornered by the ironies of my situation.

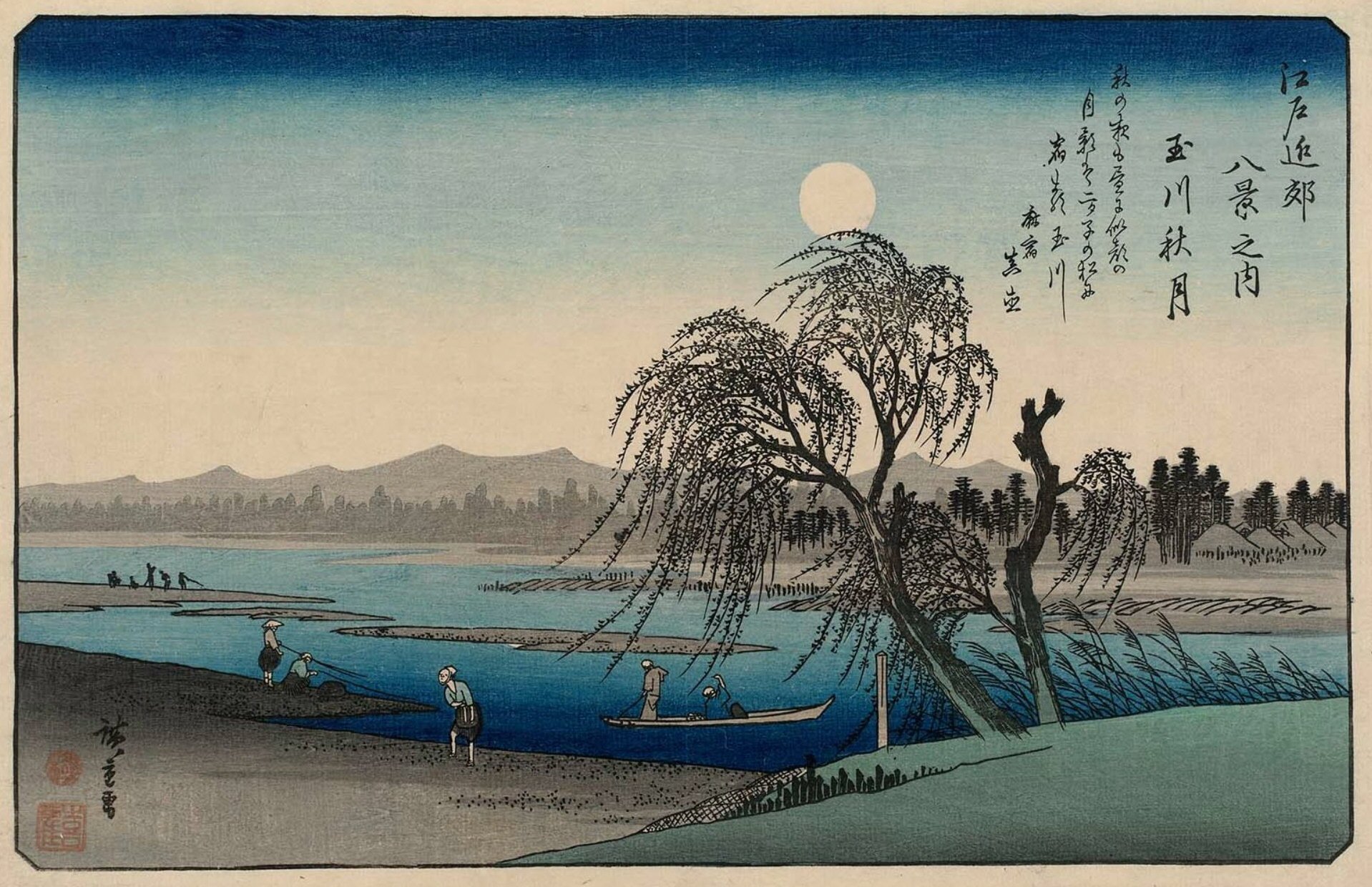

In Utagawa Hiroshige’s “Autumn Moon on the Tama River,” serene rural life is foregrounded by a willow tree.

Before I could start a family, I needed to come up with an alternative lifestyle for us, a means to protect us from the perils of modernity. But I felt cornered by the ironies of my situation. Were I to take up a job as a teacher, would it interfere with my involvement in the homeschooling of my own children? Well, I was qualified also to work from home as a software engineer, but then would I be contributing to the very technological proliferation that I wished to protect my children from? For that matter, simply having a luxurious tech salary could lure my family and me into sinful indulgence in luxury—after all, hadn’t I succumbed to such a lifestyle in New York? A full-time job at a software company, or in any office building that stifled interaction with God’s creation, was bound to tempt a man to forget that God—not money, or things, or even people—was the cause and purpose of his life. Instead, mere proximity to God’s creation offers the potential for spiritual growth. I am thinking of the haiku “The Silent Rebuke” by poet Ryôta: “Angrily I returned; awaiting me / Within my court—the tranquil willow-tree.” And so, I was drawn to homesteading. But notwithstanding the practical challenges of launching a homestead, I wondered whether the family unit by itself was enough to support a holy lifestyle.

Until the age of five, I had lived in India, where the family is one of the few remaining bastions of tradition. The mother’s tenderness is cherished, the father’s authority is respected, and the child’s obedience is nurtured. Though the nuclear family has become increasingly prevalent in that country, many Indian households are blessed with the presence of members across multiple generations. But I, an emigrant having access only to my immediate family in America, grew up feeling obligated to love uncles and aunties whom I could hardly say I knew. And when my paternal grandparents passed away during the pandemic, I could not muster a single tear.

Moreover, without the foundation of a strong community that extends beyond the family, a Christian cannot help but model himself on the indiscriminate, global community around him. Or else, he may find himself feeling terribly lonely, for he and his family are unlike others around them. This is an unnatural state of life (even if etymologically it is true that to be a saint means to be “set apart”).

I envision for my children a family that not only exceeds the nuclear but goes even beyond extended relatives. I am reminded of Plato’s understanding of justice in The Republic. We must operate as a harmonious whole—as one true body of Christ. With greater diversity of members in a community comes increased opportunity for collaboration, patience, and accountability. But what completes our diversity is our common heritage as children of God. Though Jesus is my best friend, and friend enough for me, I of course would benefit from residing among brethren who share His values.

The effort to convert a single person goes hand in hand with the mission to reform an entire society.

But is the Catholic individual to blame for his own lack of community? Well, in the words of St. Teresa of Ávila, “No one is lost without knowing it. . . . No one is deceived without wishing to be deceived.” Nevertheless, it seems to me that the present conditions of society make it all the easier for a good man to deceive himself. The effort to convert a single person goes hand in hand with the mission to reform an entire society. As G. K. Chesterton writes in his essay collection The Outline of Sanity, “If the man merely escapes from those who are slowly poisoning him, to some extent the very air he breathes will be an antidote to his poison.” Easier said than done. We find ourselves, after all, in a different century than Chesterton. “The gigantic invisible broom that transforms, disfigures, erases landscapes has been at the job for millennia now, but its movements, which used to be slow, just barely perceptible, have sped up so much” (Milan Kundera, Ignorance). Still, I am hopeful that God will bestow on His people the grace to initiate change in our world. “As each group or family finds again the real experience of private property, it will become a centre of influence, a mission” (Chesterton).

Two farmers stop their work of harvesting potatoes to pray the Angelus in this painting by Jean-François Millet.

I’ve hardly scratched the surface of my new life as a homesteader.

My hope has only grown since joining Our Lady’s Ranch. My friends and I do honest work amid God’s creation, generating goods that people need and value, while providing for much of our own healthy diet, and ultimately finding that God’s gifts are so bountiful that we are able to share them generously with our neighbors.

My primary work as a member of the ranch is to spread knowledge about the homesteading movement which has been gaining traction across our nation and the world. I accomplish this in large part by representing our Catholic agrarian family lifestyle through photos, videos, and blog posts. But even when I’m helping to feed our animals and maintain their shelter, or to pack meat and deliver it to our customers, I always find contentment in my faithful stewardship of God’s creatures.

Pray, Work, Play

And when we aren’t working, we’re either praying or getting a healthy dose of play. Our daily schedule is structured around community prayer, beginning with morning meditation, punctuated by the Angelus at noon and the Divine Mercy Chaplet at three o’clock, and settling down with grace before dinner. We each practice our own personal devotions, too. And there is always time for simple pleasures, like playing board games together, enjoying s’mores around a fire, or simply picking fresh eggs at night under a starry sky.

My journey at Our Lady’s Ranch has just begun, and I’ve hardly scratched the surface of my new life as a homesteader. But I am confident that God is leading me along His strait and narrow path, on a direct course to Jesus within Our Lady’s Ranch, through His magnificent creation, Mary 🙂